Eurovision voting data could hold the key to unlocking the roots of the United Kingdom’s suicidal notions of exiting the European Union.

Introduction

A topic that has been consistently in the headlines in Europe over the past few months has been the UK’s imminent referendum on whether or not to abandon the European project that has dominated the politics of this continent for the past seven decades. On June 23, citizens of the UK will vote in a referendum on the topic, and the result of this referendum could have a major impact on both the UK and Europe for decades to come. While a vote to remain inside the European Union is expected, the polls show that the result could go either way. This is despite the fact that evidence exists that a “Brexit” from the EU could have serious adverse consequences for the general UK population. Indeed, the OECD estimate that Brexit would equate to a loss of one month’s income for the average UK citizen by the end of the decade. The UK Treasury’s estimate is even worse, equating Brexit as a tax of two month’s income for every inhabitant of the country. US President Barack Obama said in plain terms that a Brexited UK’s bargaining position with regards to major trade deals would be put back by a decade. David Cameron has intimated that Brexit would invariably lead to war and genocide on the continent, while scientific researchers have protested that leaving the EU would inhibit their efforts to stop cancer spreading throughout the United Kingdom. Brexit won’t cause cancer, but it certainly won’t help either.

Despite this, the threat of taxation, war, genocide and cancer does not seem to bother the significant number of UK voters who intend to vote ‘leave’ in the upcoming referendum. The sheer audacity of such reckless abandonment of personal and global safety begs the question of what exactly the European Union did to the UK to hurt it so much to make it feel this way. The standard explanation of UK/British exceptionalism within the EU is that Britain still thinks of itself as an empire, and that this idea can never be resolved within a power sharing multinational bloc such as the European Union. While this narrative does explain the arrogance, it doesn’t explain the hurt. It doesn’t explain the deep wounds that Europe inflicted on the UK to push it to the point where it was willing to risk world peace, and an end to cancer, just to break away.

A main facet of economic theory is that in order to reach as valid a conclusion as possible, we must search for revealed preferences, rather than stated preferences. What this means is that we do not ask people what they think (stated preferences), but we search for things that might show what they think (revealed preferences), or possibly how they feel. Asking a UK citizen why they are voting yes/no in the upcoming referendum might provide insight into the issue, but it doesn’t reveal what we want to show: the hurt.

The best resource to show UK attitudes to Europe, and vice versa, is probably the Eurovision Song Contest (ESC, or more commonly ‘the Eurovision). Every year the UK provides an entrant to the competition, and other European countries award points based on quality and other factors (such as borders). In turn, the UK gets to award points for it’s favourite songs from other European countries. While throughout most of its existence the Eurovision’s voting procedure involved a professional jury dictating the merits of each song and awarding points where warranted, a significant change occurred at the turn of the century as televoting has been introduced, and democracy with it. By law the Eurovision must release all its voting data to the public, and therefore a rich dataset exists that perhaps can give us some insight into the UK’s relationship with the rest of Europe, and perhaps some revealed preferences.

The UK & The Eurovision

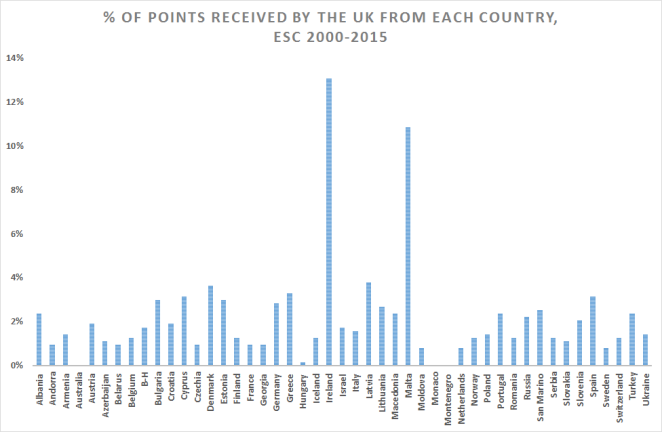

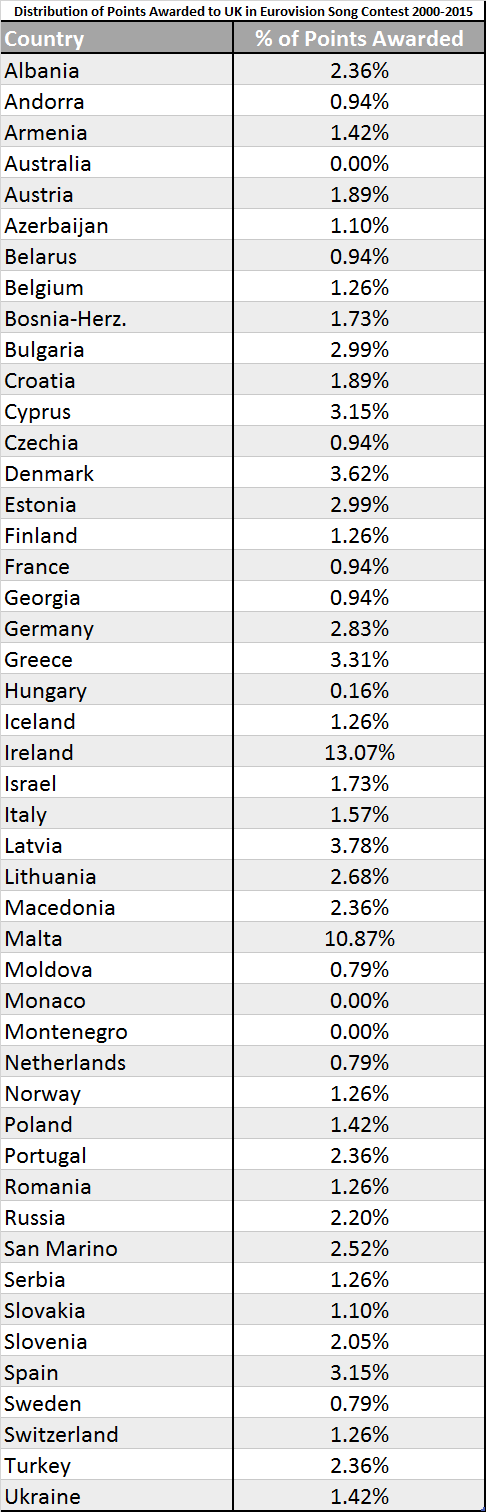

In the time period 2000-2015, 48 countries have participated in the ESC. Most of them are European, while also countries such as the Caucasus nations (Georgia, Armenia & Azerbaijan) and Israel have been granted access, as well as Australia in 2015. This means that the populations of 47 nations (the UK cannot vote for itself) have had the opportunity to award points to the United Kingdom over the past 16 Eurovision Song Contests. Over this period, the UK received 635 points from these nations, out of a possible total of 4224 (Caveat: I didn’t feel like calculating this, but the formula would be something like {16*(12*(nt-1))}, where nt is the number of participating countries in the Eurovision that year. The minimum number in the data set is 23, so I am using that minimum.). The percentage share of each participating country in this total of 635 points is detailed in the table below.

If you weren’t bothered reading all that, then the graph below should do the trick.

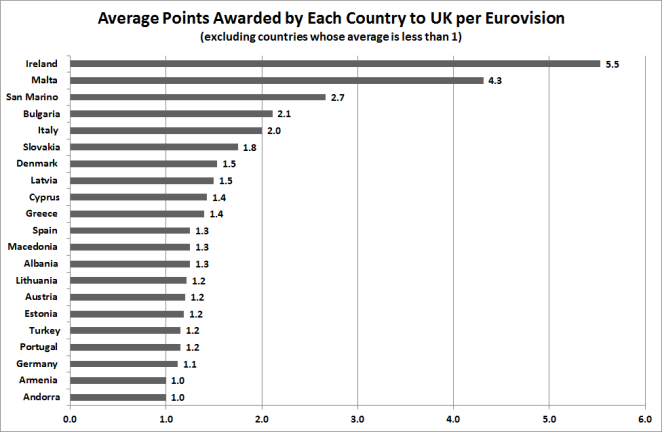

Ireland and Malta obviously stand out. These are two very small countries, yet combined they are responsible for almost 25% of the UK’s total points in this time period. To put this in starker terms, the below graph shows the average points each country awarded the UK between 2000 and 2015. The maximum number of points awardable is 12.

Ireland will give an average of 5.5 points to the UK in each Eurovision, while Malta will give 4.3 points. Then there is a sizable drop in the level, and the average of most countries points awarded to the UK is too small to appear on the graph.

Malta and Ireland are obviously different than the rest of Europe, and that difference is not that they are both islands, but that they are very recent colonies of the United Kingdom. There is an obvious cultural heritage in these countries that the rest of Europe does not share, as well as the presence of a multitude of UK expatriates who can contribute to the televoting figures from these countries. An argument may be that Ireland and Malta are the only two other English speaking countries in the Eurovision Song Contest, however anyone who has seen the Contest knows that most songs are in English these days anyway.

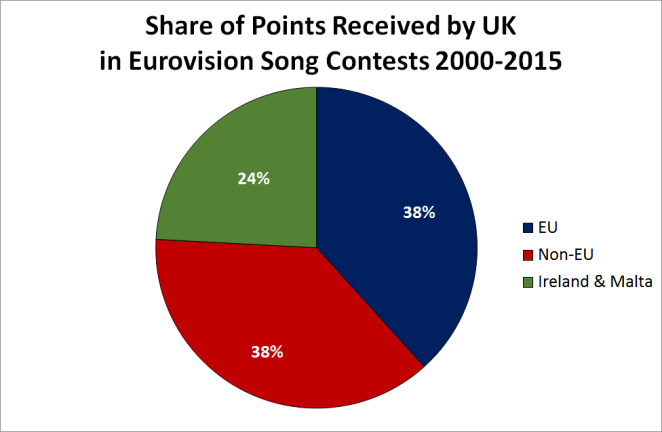

How does Europe react to Britain if we exclude Ireland and Malta? The chart below separates these two countries from the pack, and groups the remaining countries into EU and non-EU designation. EU expansions in 2004, 2007 and 2014 have all been accounted for.

The UK this century has received an equal share of points from the EU (excluding Ireland and Malta) and Non-EU countries. 38% of its points have come from European Union member states that were not formerly under the rule of the British Empire.

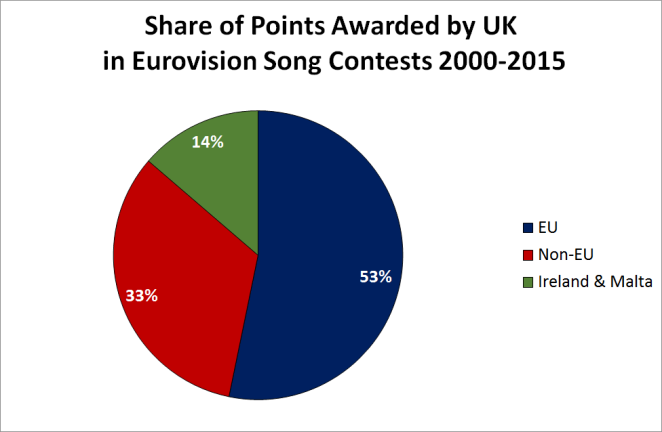

While Europe (both EU and non-EU) have a balanced opinion of the UK in the Eurovision Song Contest, with each contributing 38% of its total points haul, it is worth looking at things from the the other side: how has the UK voted in this period? Cutting right to the chase, and using the same methodology as before (grouping EU, non-EU and Ireland/Malta as three distinct categories), the results are in the pie chart below.

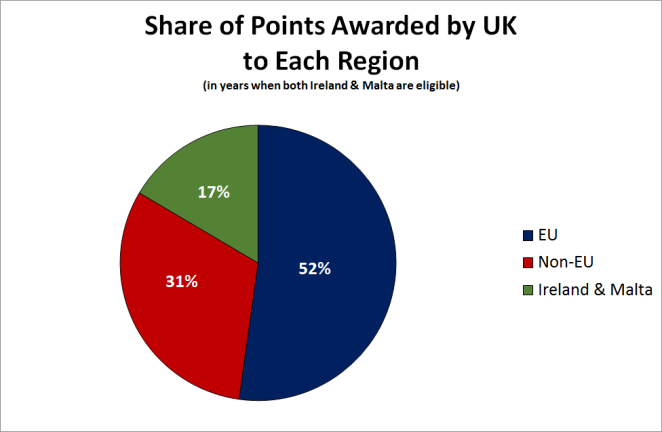

Things are different here. Ireland and Malta receive just 14% of the UK vote, while the EU is substantially preferred, beating non-EU countries by twenty percentage points. At this point, it must be said that not every country can be awarded points in a Eurovision final, but merely those countries that proceed to the main competition. On several occasions in the time period, Ireland, Malta or both were absent and therefore ineligible for points from the UK. The chart below accounts for this, using only data for when both countries were present.

This does little to account for the discrepancy between EU points awarded to the UK, and UK points awarded to fellow EU nations.

Conclusion

The analysis of Eurovision televoting data showed that if we exclude the former British colonies of Ireland and Malta, EU nations have contributed 38% of the United Kingdom’s points total. In contrast, the UK itself shows a marked preference for the European Union, with 53% of its points going to the bloc, again excluding Ireland and Malta. What this suggests is that there is something going on underneath the surface of the relationship between the EU and the UK, and it is something that only can be seen in this data.

Britain/The Uk/Whatever is a small country in the world. It was big and popular once, but now is quite unsure of itself. It acts like it has confidence, and can succeed independently, but is really quite dependent on its smaller friends to provide an ego boost. The UK has sent gushing approval to the EU and Brussels over the past 16 years, and it has not received the same signals back. The UK clearly favours the EU, as is apparent from its voting patterns in the Eurovision data, yet the EU’s acceptance of the UK is far less clear. Perhaps Brexit is not about fantasies of lost empire at all. Perhaps it is but a tale of unrequited love, a call for attention from a secret admirer who only wants some tender loving care, but is far too proud to show it. Brexit is the political manifestation of a population that is accustomed to listening to Adele albums on repeat: they are ready to risk genocide, war and cancer just to seem relevant and loved. Maybe in this year’s Eurovision, we should requite some love: vote for the UK on Saturday. Before they set fire to the rain.